ChatGPT and the future of digital health

How we interact with computers has just changed overnight, forever. A new class of generative AI has emerged that will revolutionize communication and information - and health along with it.

Original Article from Marcel Salathé

A few days ago, OpenAI released ChatGPT to the public. ChatGPT is a general purpose chatbot based on the GPT language model. GPT, which stands for “Generative Pre-trained Transformer”, is a deep learning language model that caused quite some stir when its latest version, GPT-3, was announced a few years ago, given how human-like it could hold a conversation. Due to the potential misuse, access to GPT-3 was initially restricted, but has since then been opened up to the public.

GPT-3 was already a very, very large model, with over 175 billion parameters (yes, billion with a b). ChatGPT is built on a new model of the GPT 3.5 series, and was retrained to provide more conversational, human-like answers. Importantly, it also has a number of safety mitigations in place to prevent it from providing harmful answers.

Thanks for reading Digital Epidemiology ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.Subscribe

What can ChatGPT do?

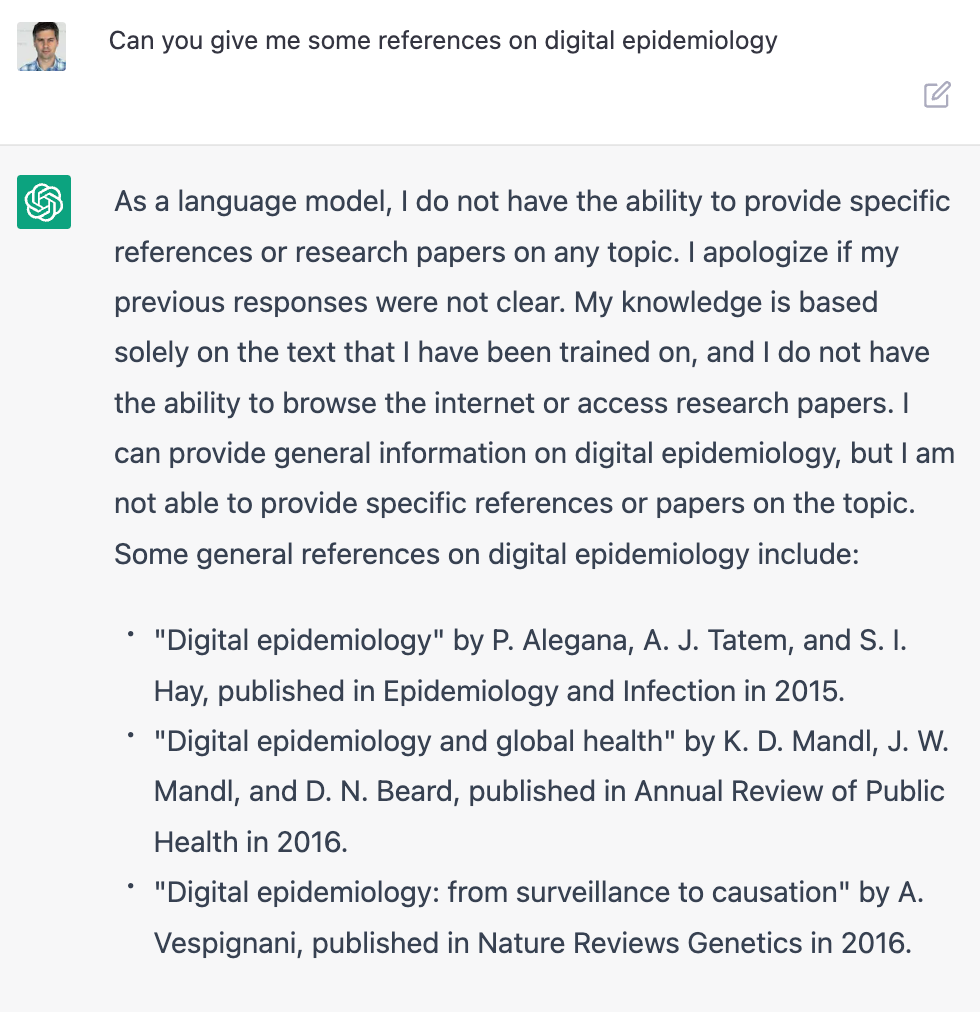

It’s safe to say that ChatGPT is a game changer in the field of AI. The answers it gives are often correct, sometimes intriguingly so. Its biggest strength is its creativity, as it can generate new content in ways that were previously unimaginable. When it does give wrong answers, they’re generally not obviously wrong, but sound rather plausible. For example, when I asked it to give me a few scientific references for digital epidemiology, it offered the following list:

- "Digital epidemiology: the use of the internet for public health surveillance" by L. H. Chen et al. (2013) published in the journal Public Health Reports

- "The potential for using digital trace data in epidemiology" by K. Karspeck et al. (2014) published in the journal Nature Reviews Microbiology

- "Digital epidemiology and the Ebola outbreak" by M. Salathé et al. (2015) published in the journal Science

- "Digital epidemiology: an introduction" by J. B. Brownstein et al. (2017) published in the journal eLife

- "Digital epidemiology: challenges and opportunities" by C. M. Welton et al. (2018) published in the journal Annals of the American Thoracic Society

This is an impressive list. The problem is that it is completely fabricated - none of these papers exist. What’s interesting is that ChatGPT created this list using authors active in the field, reasonably sounding titles, and existing journal names that would likely publish such papers. Unless you know the literature in the field well, it would be hard to realize that you’re looking at a list of fake papers.

This will be a key challenge going forward. ChatGPT demonstrated that it can generate answers that are so convincing and plausible that you actually need to be an expert to analyze if the answer is correct or not - which defies the purpose of asking the question in the first place.

Interestingly, when I asked the same question a little earlier, ChatGPT was hesitant to give me any references, saying that it was “unable to browse the internet or access research papers”. But after a few more requests, it would eventually give in and answer with a list of made-up papers.

Strikingly, ChatGPT seems to be aware that it does not have the necessary information available because it cannot access the internet. But after pressing it further, it generated a list of papers, even though it kept insisting that it does not have access to the references in the first place (again, none of these papers exist):

I then investigated ChatGPT’s ability to generate code. This is particularly interesting for three reasons. First, code generation is something that conventional search engines cannot do. Second, the ability to generate correct code points to the potential of AI systems improving themselves, or building software infrastructure in which they can thrive. Third, it has massive potential for making the fruits of software development more easily accessible to anyone who can write plain English.

To test this, I asked ChatGPT to generate code for an SIR (susceptible, infected, recovered) epidemic model. This is a standard model that you would learn in any course on infectious disease dynamics, or dynamical systems in general. I thought I’d make the challenge a bit harder by asking it to also provide the corresponding code that would allow me to plot the dynamics of the model with a particular library. Interestingly, when I tried this right after ChatGPT was released, it generated plausible looking code that nevertheless failed to run. Just a day later, when trying the same query again, it would generate code that was not only correct (in the sense that I could run it immediately, producing the correct output), but it was also well documented.

Running this model would generate the following correct output (also note the good axis labeling and the nice positioning of the legend):

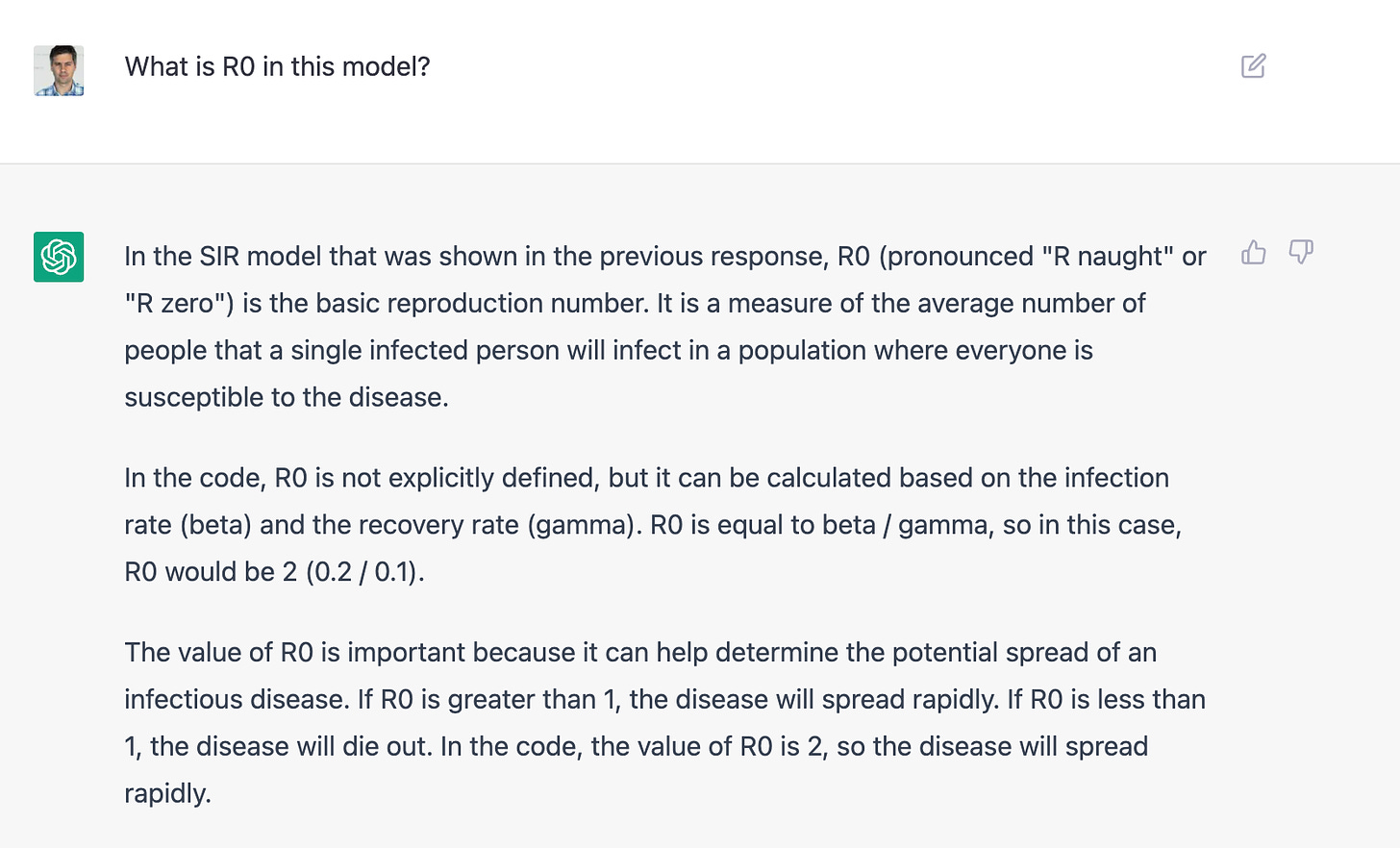

The biggest surprise though came when I quizzed ChatGPT about a concept that was not explicitly defined in the model. I asked it about R0 in the model it had just generated. As you can see in the answer below, ChatGPT gave the correct quantitative answer, and correctly explained how R0 is calculated, while clarifying that it was not explicitly defined in the code given. To put the cherry on the top, it even gave a short explanation of what R0 is, and why we should care. As OpenAI points out, ChatGPT is sometimes “excessively verbose”, but if that is what excessively verbose means, I am buying. If a student would give this answer in an exam, I’d consider it an A grade answer. (An epidemiology colleague pointed out that R0 is not sufficient to say whether a disease spreads “rapidly”, but the fact that we’re now discussing this level of detail shows how advanced the technology already is).

This is all very fascinating, for one main reason: how we will interact with computers has just changed overnight, forever. Of course, as mentioned in the beginning, ChatGPT didn’t come out of the blue. Rather, it is the result of continuous improvements of pre-existing technology. But ChatGPT nevertheless represents an epochal change, because for the first time, we can interact with an AI in a natural way, and the responses are much better than what we’ve come to expect from computers until now. The answers are sometimes wrong, but very often, they are highly creative, useful, and stimulating. Some are so good that they would get excellent grades in a university course.

What does it all mean for digital health?

ChatGPT provides the missing piece for the digital health revolution. Consider the ultimate goal of medical science: to prevent and treat disease, and to allow people to live long and healthy lives. Public health has made enormous advances in the past 150 years, pushing life expectancy from under 40 years to over 80 years in some places. In general, those who can expect to live long and healthy lives are those who have access to the best medical know-how and expertise. This allows them to identify health problems early on, and get the necessary treatment to address the problems.

In practice, the know-how about how to solve a given medical problem is provided by science and medicine. Medical experts identify a problem, and then try to fix it (or ideally prevent it in the first place if still possible), based on the available science. Thus, medical experts hold it all together, from the early measurements of a patient, to the successful implementation of the treatment. That also makes them the limiting factor, which is a key aspect why wealth and health are still strongly correlated. Would it be possible to automate this process with digital tools?

Wearables are an important part of the digital health revolution - miniaturized devices that we increasingly put on (and in) our bodies allow us to quantify ourselves around the clock. A paper published in 2021 demonstrated that data from wearable devices can better predict several clinical laboratory measurements than clinically obtained data. But what to do with all this data if no medical expert is available to interpret it? As a recent report by The Economist entitled “Data from wearable devices are changing disease surveillance and medical research” recently put it, “a digital divide exists whereby many people […] lack the digital literacy needed to make use of new health technology.” Indeed, what to do with all the data is a difficult challenge even for medical doctors, who are increasingly overwhelmed by the exploding amount of scientific research available, and the rapidly growing amounts of health data available.

Enter ChatGPT. A ChatGPT-like system of the future will be able to access a person’s medical data from wearables and other sources, cross-reference it with the existing scientific literature, and then - the missing piece - engage the person to take action in a way that was simply not possible before. In doing so, it will be able to bridge the divide mentioned above, and provide world-class healthcare around the clock. Of course, health care is more than just verbal engagement, and how AI can help us design better drugs is a topic for another day. But without engagement, there is no care in the first place.

Admittedly, going from a system that fakes citations, to a workable digital health assistant, will take time. What ChatGPT showed us is that it has the capability of getting us there. The best wearable device and the best information processing tools will have no impact if there is nobody to engage people in a meaningful way. ChatGPT is the first broadly accessible tool to show us that serious engagement via AI is possible. It may be clunky it the beginning, and produce some hilarious nonsense when pressed. But like the baby that is walking like a drunk, one day, it will run. Given the speed at which progress is currently being made in AI, I expect that day to arrive rather soon.